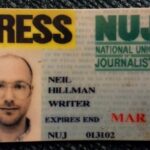

The one in which Neil loves his work in the heartland…

Halcyon days.

The world was a very different place in 2018 (or 2BC as I have come to think of it: i.e., two years Before Covid). Because no one, except for those who accept the fanciful theory that a handful of malevolent and scheming protagonists arranged the virus, could have possibly imagined the breathtaking, totalitarian measures various governments quickly implemented in response to it; nor quite how much damage these strategies – designed to manage and control the movement and liberty of their own citizens – would subsequently wreak on the health and wealth of every man, woman and child who lived through 2020 to 2022. It’s a period I have also given a name to: The Great Repression.

One notable exception to this sweeping act of repression was Sweden, who declined to shut down their economy or lock-up their citizens; and yet they still managed a lower death rate from Covid than the United States and the United Kingdom, numbers 1 and 2 respectively in the Coronavirus ‘hit parade’. (Source: https://www.flowmetric.com/cytometry-blog/retrospective-review-of-swedens-approach-to-the-pandemic )

At the time of writing this, (September 2022) England has recorded 20 million cases of Covid and has 176,000 attributed deaths (0.88% of those who contracted Covid, died). For the UK as a whole, 23.7 million Covid cases were recorded, with 207,000 deaths (0.87% of those who contracted Covid died). (Source: https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/coronavirus-data-explorer)

In Australia, the figures are even lower: 10,244,727 reported cases resulted in 15,234 deaths (with not of Covid – the statistics table makes this distinction, not me), which is a mortality rate of just 0.15%. (Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/australia/)

I don’t want to down-play the serious nature of Covid-19 for those who contracted it, especially for those compromised by other health issues; but I would like to consider for a moment the almost incalculable economic and mental health costs of the measures that were imposed, in the name of the pandemic; and reflect on the time it’s likely to take to get the world back on an even keel and have civil liberties restored. Because these are the enormous consequences of the ‘state of emergency’ responses to a disease with a mortality rate of considerably less than 1%.

Surely it can’t be so clear-cut an issue as I’m painting it, (even at this distance I’m sure I can hear second-born, my PhD researcher epidemiologist son, sighing as I write this), but I ask the question anyway as this table of human mortality rates ranks Coronavirus Disease 2019 at a rather lowly 54th; behind things like Hepatitis A (53rd), Measles (51st) and Diptheria (44th). (But best to avoid Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies and Rabies, which rank 1st and 2nd on the list. Once they’re contracted and established, they’re 100% deadly.)

All of which is a long-winded way to explain why I look back to 2018 as a halcyon time, not least of all because that year I was fortunate to be working in Australia on the beautiful Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games; and I had a fabulous time, working alongside some exceptional people.

Durban dreams.

Back in September 2015 (or 5 BC), it was Durban that was awarded the hosting of the 2022 Commonwealth Games; but in March 2017 it was stripped of this right by the Commonwealth Games Federation, after a series of missed deadlines and financial guarantees highlighted the burden that comes with the prestige of hosting such an event on the world stage. It was a blow to Durban, but also to Africa: the Commonwealth Games had never been held in an African country. (As it happens, neither have the Olympic Games. Make of that what you will.)

In June 2017, Birmingham went head-to-head with Liverpool in the UK and Victoria in Canada to be the stand-in host when the call went out for alternative cities to put themselves forward. Birmingham’s bid – with 95% of the required sports venues already in place – won UK government support over Liverpool; meanwhile, the Alberta government decided to not support Victoria’s bid. And so it came to pass that Birmingham got the nod.

But it was not necessarily met with widespread approval by the residents of Birmingham at the time – that summer a 3-month refuse workers strike had left the city awash with rubbish: if the council couldn’t organise bin collections, how would it manage the Commonwealth Games, locals asked not unreasonably. Cost was another concern: the city council had been revealed as being all but bankrupt. Hosting the Games was budgeted at £750m, with a generous £560m coming from central government, but that still left Birmingham with having to find £190m from somewhere. With money desperately needed in other areas, for fundamental issues like education and transport infrastructure, had the council got its priorities right?

Ian Ward, leader of the council and chairman of Birmingham 2022, said he could understand the scepticism in certain quarters, but he promised the Games would not have an impact on day-to-day services for local people. In December 2017 he said to the Guardian newspaper:

“The Games will have huge economic benefits for the region. We expect it to create 22,000 more jobs over four years. It will also reset the profile and image of Birmingham. We are a modern, cosmopolitan city, the youngest in Europe and we’re very diverse and we want to show that off.” (Birmingham officially named as 2022 Commonwealth Games host city, The Guardian, 21/12/17)

From a publicity and tourism point of view, the benefits presented from hosting the Games were hard to argue against. It is the biggest multi-sport event in the world outside of the Olympics, with more than 5,000 athletes competing in 18 different sports; and a study by Price Waterhouse Cooper projected an increase of between 500,000 and one million visitors to Birmingham on each of the 11 days of the Games. In any case, with Birmingham preparing its bid for the hosting of the 2026 Commonwealth Games, it looked like a much-needed boost to Birmingham’s image and stature could arrive 4 years earlier than anticipated. Still, everything hinged on it going well; and of course, the financial costs would be scrutinised minutely.

Days of Empire.

The British Commonwealth consists of 52 countries, although the Commonwealth Games Movement recognises 72 nations and territories. Each of these nations or territories has a Commonwealth Games Association and each of these Commonwealth Games Associations have exclusive authority to send athletes to participate in the Commonwealth Games.

Inspired by the Inter-Empire Championships, which were part of the 1911 Festival of Empire, Melville Marks Robinson founded the Commonwealth Games in 1930 (held in Hamilton, Canada) but until 1950 (Auckland, New Zealand) they were called the British Empire Games, a clear link to Britain’s colonial past, an increasingly uncomfortable part of our history and an aspect that is underplayed in favour of the Games more meritous mandate to bring harmony to the diverse territories and nations that make up this Commonwealth alliance.

They became the British Empire and Commonwealth Games in 1954 (Vancouver, Canada) until 1966 (Kingston, Jamaica), the British Commonwealth Games from 1970 (Edinburgh, Scotland) to 1974 (Christchurch, New Zealand) and then simply the Commonwealth Games in 1978 (Edmonton, Canada), to reflect changing sensibilities and to accommodate how Britain manages its colonial history; but one unofficial name that has remained a constant is ‘the friendly games’.

For all that in its back story, it’s a progressive sporting movement: athletes with a disability have been included as full members of their national teams since 2002 (Manchester, England), making the Commonwealth Games the first fully inclusive international multi-sport event; and at Gold Coast 2018, the Games became the first global multi-sport event to feature an equal number of men’s and women’s medal events. Four years later – in Birmingham – they were the first global multi-sport event to have more events for women than men.

And regarding the thorny issue of Empire, in his thoughtful essay entitled Commonwealth Games must confront the truth about its sportswashing past, Andy Bull asks an important question: ‘Once the usual legacy promises about urban regeneration and sports participation are stripped away, what value do the Games have unless they’re part of a genuine attempt to reckon with our own unconfronted history?’ (Andy Bull, Guardian, 28/07/2022)

The official line and pre-prepared answer is, I think, a totally positive one and one that I’ll happily sign up to, because I believe passionately in the redeeming nature of sport and its uplifting Corinthian spirit:

‘Today, the Commonwealth Games Federation is far more than the curator of a great Games. As a cornerstone of the Commonwealth itself, our dynamic sporting movement – driven by its values of Humanity, Equality and Destiny – has a key role to play in an energised, engaged and active Commonwealth of Nations and Territories.’ (From The Commonwealth Sport Movement website)

Money, money, money.

Clearly there is a political element to every major sporting event. The kudos for a country or a region showing itself off to the outside world is enormous, which is why regimes with dodgy human rights records (for instance China), or a propensity to unfairly advantage their athletes (for example Russia), clamour to distract the world’s attention with something more wholesome than their day-to-day way of going about things.

This always gives rise to questions over possible corrupt practices to secure events like Football World Cups: the awarding of the 2018 and 2022 World Cups to Russia and Qatar for instance is surrounded by claims of officials being bribed to vote for certain countries – as reported by the New York Times: U.S. Says FIFA Officials Were Bribed to Award World Cups to Russia and Qatar, (Tariq Panja and Kevin Draper, New York Times, 20/10/2021)

Similarly, the awarding of a Formula 1 Grand Prix held in Russia in 2014 came at a time when the then President of Formula 1, Bernie Ecclestone, was being prosecuted for paying a $44m bribe to a German banker, and Formula 1’s usual ethical oversight for host countries was suspended in Russia’s case. It was later revealed that criticism of the decision in favour of Russia was well-founded, when a catalogue of corruption surrounding the building of the infrastructure required to host the Formula 1 race came to light: not only did the event provide a global audience of 1.5 billion and allow Russia to present a more palatable side to Vladimir Putin’s oppressive governance, the companies carrying out the work were all run by Putin cronies. (Katherine Kennedy, Greasing the Wheels: How Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund Ended Up Financing Russian Corruption, The Global Anti-Corruption Blog, 19/09/2022)

And of course, the granddaddy of them all, the Olympic Games, is no stranger to controversy, political and financial. Both Rio (2016) and Tokyo (2020) had protesters taking to the streets opposing the money that was required to host the games (and there’s even a page on Wikipedia devoted to the List of Olympic Games scandals and controversies.)

So apart from the furore surrounding the corruption engaged in by local officials of the Delhi 2010 Commonwealth Games, (Ravi Shankar and Mihir Srivastava, Payoffs & bribes cast a shadow on CWG, India Today, 07/08/2010) it would appear that the Commonwealth Games has commendably managed to avoid the distasteful depths of financial opportunism that other events have been plagued by.

With a characteristic sense of understatement, Birmingham 2022’s greatest controversy was the unpopular decision to demolish the landmark Perry Barr flyover. (Graham Young, Perry Barr flyover to be demolished even though athletes village plan axed, Birmingham Evening Mail, 12/08/2020)

Happiness is a warm Brum.

This year, the summer turned out to be a sizzler for the UK. Thank goodness. There needed to be at least some relief from the relentless bad news that had shrouded the country from early spring.

Energy costs had risen by 54% in April, and were due to increase by an eye-watering 80% in October; inflation had reached double-digits with a prediction of an 18% inflation rate by January 2023. Which fuelled suggestions that come the winter, British families would be facing a stark choice: whether ‘to heat or to eat’.

With inflation rising, so too did interest rates; and to add to the government’s misery (and the rest of the country) some workers who were frustrated at pay rises that amounted to pay cuts in real terms, started to strike – and first out of the blocks were the train drivers, dockers and postal workers. The prospect of the forthcoming winter was not an alluring one.

But for now, with the sun blazing, folks flocked to the beaches… Only to be told that water companies were pumping raw sewage straight into the sea at 50 of the nation’s favourite beaches. Southern Water, Wessex Water and South West Water were amongst those reported to Ofwat, the water regulator, for being involved with the discharge of untreated sewage into the sea at popular swimming areas along the south coast (but it affected more than just the south coast); all the more disappointing given that Southern Water was fined a record £90m for doing exactly the same thing last year.

Unsurprisingly, the spotlight was brought to bear on the UK’s privatised water companies, in particular at the amount paid to shareholders – £500m in 2021 – compared to the investment that found its way into the repair of infrastructure that could prevent the discharge of sewage to the sea, as well as droughts, leaks and hosepipe bans. The Tory miracle of ‘market forces’ was starting to look anything but miraculous; and patience was wearing thin at a Conservative government that with monotonous regularity had been caught cooking the books, rather than balancing them.

Things were becoming desperate in Downing Street. ‘Operation Save Big Dog’ – Boris Johnson’s all-out attempt to cling to power, masterminded by the Australian political strategist Lynton Crosby – was clearly approaching its dog-days: a term that journalists often use to describe the lead-up to car-crash exits by political leaders, derived from the ancient Greek belief that as summer approached and the rising of Sirius appeared alongside the sun, the heat generated from the two stars would create catastrophic events on earth.

The Romans adopted this mythology and called it dies caniculares, or ‘days of the dog star’, which eventually became known as ‘dog days’ – a phrase fittingly utilised for this ‘Big Dog’ Prime Minister, one so shamefully exposed as a liar, so lacking in integrity and so wont to rely on quoting obscure Latin phrases from his studies of Classics at Eton, that the summer of ‘22 would prove to be a humiliating, ignoble and inevitable end to his premiership. Sic semper tyrannis.

But before he was forced out of office by his own kind, (and on a brighter note for the rest of us), the weather remained consistently beautiful for the 11 days of the Commonwealth Games; reassuringly, held at inland venues well away from dirty beaches.

Reduce, reuse, recycle.

I’m bashful to admit it, but in the spirit that these blogs are written as un-sanitized warts-and-all accounts, I will: it came as a huge relief to start my engagement for the Commonwealth Games. There we are, I said it.

In my previous blog, The Changing of the Guard, I explained how my dad had died just 3 days before I started work, 16 days after having a stroke, which itself had occurred only 3 days after I arrived back in the UK. As the solitary child, it was an intense period, supporting my Mum and coordinating arrangements for both the funeral and the service. I was sleep deprived, the emotions of the people closest to me were suddenly running high and I was doing my best to keep a lid on it all.

I’m not quite sure how well I did with pouring oil on troubled waters, or whether I was simply adding fuel to the fire by speaking plainly at times. But knowing that I had to start work on a certain day helped concentrate my mind on the jobs that needed to be done first; even if going to work to mix live broadcast sound for a sports event was much more familiar ground for me than dealing with the disorientating and unexpected death of a loved parent.

The theme for Birmingham 2022 was sustainability, with the mantra ‘Reduce, Reuse, Recycle’. I was based at the NEC, in the International Broadcast Centre (IBC), and much of the basic office furniture we sat and leaned on was considered as ‘no longer needed’ and had been given a new lease of life and sourced especially for the Games. It certainly proved the point that there is an extended life in many things we routinely discard, because whilst clearly none of it was brand new, neither was any of it scruffy. After the Games, various charities identified by the B2022 organising committee would receive the furniture.

The IBC is where all the signals from the 15 Games venues throughout the region were routed back to, before being passed to rights holding broadcasters to transmit in their own territories: in the UK, that was the BBC; around the rest of the world, it included stations like Channel 7 in Australia and Sky in New Zealand. There were eight Commonwealth broadcasters who had decamped or travelled to be on-site with us at the IBC: the previously mentioned BBC Sport (UK), Seven Network (Australia) and Sky (New Zealand), plus Supersport (South Africa); Sony (India); CBC (Canada); Astro (Malaysia); and Sportsmax (Caribbean), but of course feeds were made available to all of the Commonwealth countries.

Post-Covid, new sensibilities abound with sports production and top of the list is what is known as ‘remote production’: a term used to describe when a skeleton crew attend the event with the necessary location equipment, and only a sufficient number of specialists are on-site to send the audio and video signals back to a production hub, where the rest of the production and operational team gather and the various microphone and camera outputs are received, mixed, switched and combined for transmission.

For instance, Outside Broadcast (OB) trucks covering Premier League and Championship games in the UK have for some time been sending their multiple outputs to football production hubs dedicated to the production and transmission of football matches: a base at High Wycombe looks after Premier League Productions’ broadcast distribution; and Sky’s studio and transmission base in Osterley looks after production and distribution of games to Sky Sports’ football channel subscribers.

At Birmingham 2022, where planning had started well before the pandemic struck, adaptations to accommodate this brave new world of sports production were considered; but traditional methods were still judged to be the best options: primarily because the Commonwealth Games Federation doesn’t own a remote production facility and the venues themselves lacked the connectivity required to route dozens of feeds back to a central hub. So, in a time-honoured way, the Commonwealth Games events were mixed and switched in the individual Outside Broadcast trucks at the venues, before their outputs were sent to the IBC for onward distribution to overseas broadcasters.

With a global television audience of 1.5 billion, this was the biggest sporting event on British soil for a decade; the London 2012 Olympics being the last, (and massive), event. (I was fortunate to work on Beach Volleyball at Horse Guards Parade for the main 2012 Olympic Games – the best party in town – and then at the Olympic Stadium for the Paralympics.)

The Commonwealth Games is a far more modest affair than the Olympics, though. As The Broadcasting Bridge reported the day before the opening ceremony: ‘More than 370 cameras will be deployed across 19 different sports and 22 OBs, with additional trucks needed for events like road cycling and time trials. Live coverage alone will tally 1500 hours with additional material including a best of games channel and a highlights package for clipping taking the total production output to 3,300 hours. Some 34 feeds will be switched at the IBC (some sports like badminton and table tennis have two games playing simultaneously and require two separate feeds) with 22 the maximum number of feeds required at peak.’

Whilst impressive, it’s still a far smaller scale event, with a much smaller audience, than an Olympic Games; and therefore it required innovative and prudent solutions to meet the Commonwealth Games’ necessarily more modest budget.

Many countries that send competitors to the Commonwealth Games can’t justify the expense of sending their own production teams, or even the cost of producing their own dedicated and comprehensive coverage for their home audiences; and so to help with this, since Gold Coast 2018, a 24-hours a day channel that commonwealth broadcasters can receive and broadcast content from, imaginatively called ‘The Commonwealth Games Channel’, has been provided; and it enjoys a huge audience in sub-Saharan African countries.

At Birmingham 2022, I was one of the two sound mixers that supervised and mixed the audio output of this live-to-air channel.

IBC, baby.

My colleague, and friend, Mark Cattell and I between us covered the transmission hours of 6am until midnight, whilst between midnight and 6am, a compilation of previously unseen event highlights played out from a dedicated server. (For those of you familiar with such things, it’s rather like the ‘Red Button’ service broadcasters like the BBC provide.)

Increasingly, broadcasters provide an online ‘on demand’ portal for significant sporting tournaments, too, and so in keeping with this, the Commonwealth Games also packaged content for this purpose; and like other major events these days, the Birmingham 2022 IBC was packed with edit suites that were each recording, logging and compiling content for later use. A dedicated voice booth was routed through our sound mixing console in the Commonwealth Games Channel sound control room to enable narration and introductory scripts to be read and recorded by various edit suites throughout the IBC.

Naturally, we also had our own voice booth for the Commonwealth Games Channel, because in essence what Mark and I were presiding over was a presentation service: the events featured on the Commonwealth Games channel – such as Lawn Bowls, Swimming, Gymnastics, Table Tennis, Athletics and so on – were all produced on site by the various, self-contained Outside Broadcast trucks that took all the field of play cameras and microphones and combined them into one television signal: the ‘finished product’ that we received, linked to and transmitted. (Inevitably, it’s not quite that simple, but more details on that shortly.)

Each morning the Commonwealth Games channel would open with a stylized title sequence that reflected the different sports and the various locations where they were being held, to welcome viewers who might have been watching the ‘overnight’ pre-recorded items. An out of vision announcer provided confirmation that we were indeed ‘live’, a narrative of what was in prospect that day, gave a round-up of the previous day’s events and highlights, measured the progress of the various countries with the latest medal table and then linked to the first event that we would be covering; at which point we took the sound and vision from the remote site.

To understand the kind of thing I do as a Mixer, it’s worth me going back over that simple opening sequence and walking you through what we typically do, and how we use the mixing console during that opening process.

Zen in the Art of Mixing Audio.

Mixing for ‘presentation’ is quite different to mixing at an event itself, where as far as I am concerned as a Sound Supervisor, I am tasked with capturing the emotion of the sporting action and the atmosphere. My PhD was concerned with the role emotions play in how we react to certain types of sound, particularly when they are placed thoughtfully alongside moving pictures, such as television programmes or in a feature film; and I developed a theoretical and practical framework that sound designers can use to give pictures more impact, or to make them more memorable. (Hey – I even wrote a book on this topic, it’s called Sound for Moving Pictures.)

Done properly, the use of sound to elicit emotion can be spectacularly successful. But in presentation mode, we’re looking for subtle, seamless junctions between audio sources: like a chauffeur driving a car with a manual gearbox and the passengers never feeling a gear change (or a pilot smoothly executing manoeuvres so your gin and tonic and dry roasted nuts don’t spill in your lap). Where they join, sound effects should blend into music and when music disappears, it should do so at the end of a phrase. During intentional pauses in an announcer’s voice over script, music or effects of the item being voiced should gently rise and fall in the gaps to keep a consistent level; but always the human voice should take precedence, and the announcer or presenter’s opening words should be as clear as their last. (The mantra I teach in the classes at my online sound academy is ‘effortless intelligibility’.)

It’s OK to skip this bit if you want… (It’s totally techie.)

Let’s take in order the opening sound operations of the station:

As the closing music comes to an end of the last item of the overnight package, have the fader open for the station’s incoming opening titles (this will be played off a hard disk video recorder / player called an ‘EVS’ machine). There were two EVS players on the Commonwealth Games Channel, but often there are 3 or 4; and each EVS machine has two stereo outputs: tracks 1 and 2, and tracks 3 and 4. You need to know which of these stereo outputs to fade up, because generally if the item you are fading up has commentary on it, usually that will be on tracks 1 and 2; ‘clean’ music and effects (i.e. clean of any speech) are usually on tracks 3 & 4.

I italicise ‘usually’ for emphasis, because at the Commonwealth Games, the only place that any of us could ever think of it being the case, that standard configuration is reversed. (This is apparently a legacy from when the BBC was responsible for broadcasting the Commonwealth Games ‘back in the day’, and, well, the BBC have their own way of doing things: like putting faders upside down so you fade things ‘up’ by pulling the fader ‘down’. (Go figure: it’s totally uninstinctive. But a man wearing socks and sandals will tell you otherwise.) The BBC are rather like I imagine the army to be – they have done things ‘that way’ since the Crimea campaign, so there’s no reason to change it now. I can still recall being told as a young engineer: ‘There’s the BBC way, and then there’s the wrong way’. (Weird; and arrogant.)

As the Channel’s opening titles start, take out completely the fader that had the overnight package on. Put your hand on the announcer’s mic fader and open it with 5 seconds to go to the end of the opening titles. At the same time press the start button on the ‘Spot On’ touch screen (a PC that hosts a multi-track music player), checking first that its fader is closed. As the opening title music finishes, fade up the music bed that will play under the announcer’s microphone. (How much you fade this up I cannot tell you. This entirely a ‘feel’ thing and I have no idea what number on the scale alongside the fader I set it to; I know it’s off the end stop, and I know it’s not fully up, but in less than a split second, without looking down, I’ll know if it’s at the right volume to sit comfortably underneath the announcer’s voice.)

The music bed will play as the announcer reads his script, but graphics tables will also be played in off an EVS machine. As the graphics animate, there will be a sound effect that plays – such as a whoosh – and remember, you’ll need to know whether this is on tracks 1 and 2 or tracks 3 and 4 of the EVS. When the woosh has played, fade out that channel, so the EVS can re-cue if required without spurious sound coming out. (The announcer and the music bed are still playing.)

The announcer is now going to link to a pre-recorded highlights package of maybe 3 minutes duration, so stand by with the correct EVS fader ready to fade up, and make sure it’s the stereo tracks that only have sound effects on them (because the track that has sound effects and commentary on it will clash with what the announcer is saying.) Fade the music out reasonably quickly – on a phrase – as the EVS sound takes over – that usually starts with a woosh too, and the announcer pauses for this, but then the effects will need pulling back so as not to drown out the announcer. Keep a hand on that EVS fader though, because at the winning moment, the announcer will pause – long enough for you to creep up the roar of the crowd – but get ready for the woosh that signifies the next sport highlights, and then pull back on the effects once more for the announcer to be heard.

At the end of this package get ready to fade out the EVS sound effects (usually items like this will finish on crowd cheers) and creep in the music bed as the announcer sets-up crossing live to an event.

Now, this really is where it gets interesting: I’ll explain in a minute how this works on the mixing console, but for now just accept that our console has two audio outputs (it has more, but for this example let’s agree it has two). On one output is what we call TVISEC (which stands for Television, International Sound [the crowd and field of play effects], English Commentary) – that’s the full ‘programme’ sound with the commentary signal that English speaking audiences would like to hear. We also output TVIS (Television, International Sound). This has no commentary, just the sound of the crowd of field of play effects, so that overseas broadcasters can add their own commentary, in their own language, if they want to.

Therefore, for every event that we feature, we have two incoming sound faders: one with International Sound on it (we label this ‘FX’), and right next to it, the fader with the full TVISEC signal on it (which we label as ‘PGM’); and we send out to our broadcast clients two signals: one with English commentary, effects and music (TVISEC) and one with just effects and music (TVIS).

(Yup… We’re still talking tech.)

Now, when we cross live to the event that we’re about to feature, and the announcer is still speaking, neither the English-speaking audience, nor the foreign language audience, will want to hear the commentators actually at the event, as they will be competing with our announcer and it will just be a jumble of voices. Therefore, as we cross to pictures of the venue, you need to keep the announcer’s mic up, fade out the music bed (so it goes out on a phrase, please) and creep in the International Sound of the venue (that’s just the crowd and the effects). Now, this is the tricky bit. At some point, the announcer will finish and you’ll fade him out (both of the Commonwealth Games Channel announcers were male), but we’re not yet hearing the commentators at the event (we’re still just listening to the effects). If you were to now fade up the commentators, ‘blind’ as it were, you might get lucky and find a space where they’re not saying anything; but almost certainly they’ll be in the middle of a sentence, and halfway through an explanation of something that will make no sense whatsoever to the viewers at home.

So, we keep the International Sound going, but ‘pre-fade listen’ (PFL – a method for listening to a signal before it is faded up to a mixing console’s output) to what the commentators are saying on the closed TVISEC fader. We do this by pulling back against the end stop of the fader we want to PFL (in this case the TVISEC) and when we hear a gap in the commentators conversation (and that pause should also be judged to be at the logical conclusion of what is being said, so listen carefully) instantly fade the TVISEC fader up, and at the same time whip out the International Sound fader next to it. Done with skill and dexterity, this switch-over is inaudible.

But – I hear you cry – what of the overseas broadcasters receiving the International Sound only? You’ve just faded out their signal! Well yes. But no.

The mixing console has two independent layers of faders (Layer ‘A’ and Layer ‘B’) and we can also make certain faders do certain tasks for us. Like getting one fader to remotely fade up another. And so here’s what we do: on the ‘B’ layer we put a second feed of the International Sound and make it controlled by the ‘A’ layer TVISEC fader. When the TVISEC on the ‘A’ layer is faded out, so too is this ‘B’ layer International Sound (we don’t need it up, because it’s up on the ‘A’ layer). But when we fade out the International Sound out on the ‘A’ layer, and at the same time fade up the ‘A’ layer TVISEC, International Sound comes up too, on the ‘B’ layer. I know, cool, huh? (It’s a bit like a conjuring trick: when you see how it’s done, it’s even more impressive.) And obviously, we duplicate this on the console for every source on the mixing desk that comes from a venue; and we repeat variations on those basic operational steps each time we cross from one venue to another, generally with the announcer leading the way, until our shift is done.

Welcome back!

Our shifts were either 06:00 to 16:00 or 15:00 to 24:00, and Mark and my days and nights were spent mixing various sound sources as required for the live output of the Commonwealth Games Channel. After a week of our 14-day booking, Mark and I swopped over. I’d had the early shifts first, which suited me as I was able to get away on one afternoon to meet with the funeral director at Mum and Dad’s house, and I also managed to unexpectedly meet-up with a dear friend for dinner on another afternoon. Earlies also suited me because on balance, I’m a morning person. One thing that didn’t suit me was, three days in, getting a call on the hotel room phone at 3 am. I was utterly unconscious, and came-to with a totally spaced-out start; thinking straight away ‘Oh god, my Mum’s died’.

I wasn’t calmed when the first thing the receptionist said was ‘Mr. Hillman?’… ‘Yes, yes,’ I replied thick with sleep but jolted awake. ‘Is everything OK?’ I continued… ‘I’m afraid not, sir’ (Oh dear god, what?) ‘You’ve ordered room service and we don’t have a credit card on file for you. Could you come down to reception right now?’ (So, my mother hasn’t died – good, calm down and be still my beating heart; but some idiot was either playing a joke on me, or the woman at the other end of the phone had got me confused with someone else – either way, it wasn’t good.)

It wasn’t good at all because I was decidedly short with her – yet illogically polite in that way we are when we’re startled or caught on the hop. (I often think that I sound remarkably, embarrassingly, like Terry Thomas when I get riled like this.) I made the point that as I was fast asleep when she called, and had to be up for work in 2 hours, why on earth would I be ordering steak and chunky chips or a Club sandwich from room service? Thus, having fully established my affronted status with her, I decided to slam down the phone.

Except the lights weren’t on in my room. And I couldn’t find the cradle for the handset. So, it took quite a few stabs in the dark for me to hang up in a huff. So many in fact, that the effect of hanging up on her would have been totally lost; and unfortunately, if the receptionist did stay on the line, all she would have heard was the kind of paratrooper language I’d been at pains not one minute earlier to protect her from, as I flailed wildly in the night with the receiver in my hand. Oh, well. It was both of our karma, I suppose.

Unbridled joy.

Rather like Gold Coast 2018, the folk that I worked with at Birmingham 2022 were wonderful. We quickly gelled and became a close knit team: a director, a producer, an EVS editor and an announcer for the day shift, and then a different team for nights; and when Mark and I swopped shifts, so did everyone else, which was great – it meant we stayed with the team we’d started with all the way through.

I was present in the sound control room for the opening ceremony, although it was Mark who took care of the links and lifted up the magic fader carrying the audio from the Alexander Stadium. (I often say that mixing comes down to just one thing: and that’s getting the right fader up at the right time). But the closing ceremony (and indeed the closing down of the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games Channel) was down to me; and what a ceremony it was: if the opening was spectacular, and set a fabulous tone, then the closing ceremony was a total triumph… Not since 2012 had Britain so proudly told the world who it was. But this wasn’t Britain speaking, it was Birmingham; and what a message it gave: of a past that was steering the present, and of a future built on the bedrock of what had gone before. Industry, community, culture… And then Ozzy Osbourne made a surprise appearance to help tell the 30,000 in the stadium – and the rest of the world – that Heavy Metal music was born right here, in Birmingham, through the unique guitar playing of Tommy Iomi, Ozzy’s long-term collaborator in the group Black Sabbath. Never mind that Ozzy looked like death warmed up – he’s looked like that since he was 20… The crowd went wild, the animatronic Bull became a world-wide celebrity and Birmingham, at last, stepped out from the shadows of being the second city. In 2022, this summer, it had earned the right to believe it was the first.

Qualified success.

As it turns out, the early auditing bears out the anecdotal evidence: and the story that the first round of analysis tells us is what everyone who’d been there already knew – Birmingham 2022 was the best Commonwealth Games ever.

Specifically, hosting the Commonwealth Games, the best attended Commonwealth Games of all time with 1.5 million tickets sold, brought Birmingham to the forefront of people’s attention (and not only around the Commonwealth, 134 countries around the world broadcast the opening ceremony); and not even the London 2012 Olympics were able to boast what Birmingham managed to do in its opening ceremony: to have a local, who just happened to be a Nobel Prize winner, addressing the audience. (The wonderful Malala Yousafzai, who Heather and I got to know personally by her visits to our home, as well as to the Audio Suite studios, in the UK to promote her work as an educational activist for women.) No wonder then that the opening ceremony was streamed from the BBC website a remarkable 57 million times in the UK alone.

It was said that half of the UK either tuned in, or turned up, to the Games. At times, 20 million UK viewers were watching from their living rooms, on their tablets, or on their phones. The event created 40,000 jobs and skills opportunities for local people, including 14,000 volunteer positions, and a dedicated Jobs and Skills Academy invested over £10 million to train unemployed residents to take advantage of Games-time roles.

All of which makes the government’s Department for Digital, Media, Culture & Sport’s report on the impact of Birmingham 2022 happy reading.

In his independent paper An Early Assessment of the Economic Impact of the Birmingham Commonwealth Games, Dr. Matt Lyons from the University of Birmingham estimates that the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games will lead to an increase in output of £346 – £518 million in the region, and an increase in Gross Value Added (GVA) of £167 – £251million.

So who won?

In human terms, we all did. Without a shadow of doubt, Birmingham 2022 was a triumph of community and of endeavour; and the Games heralded an emphatic return to the joy and general feeling of well-being that is generated by such large-scale sporting festivals. Every day at the NEC, walking in the sunshine, I saw children, teenagers, couples, young families, grandparents, groups from sports clubs; all smiling, and all carefree for the time that they were there, with sport doing it’s job: providing a break from the ordinary by showing us competitors giving extraordinary performances.

In my journal at the time I wrote:

‘If there’s only one positive thing to come out of this success (although there are quite a few) it’s that Birmingham, and the region as a whole, can and should now have the confidence to step out of the shadow of any other UK city. (And it needs to stop calling itself ‘the second city’, too; that suggests something that is either second rate, second best, or both; and it turns out that it’s neither.) We’ve heard repeatedly from the commentators that Birmingham has much to commend it: more miles of canals than Venice (56 miles), more trees than Paris, and with 8,000 acres of parkland, it’s the greenest city in Europe. It’s also the youngest, with 40% of the population below 25 years old. If I were a politician, and it was my desire to foster and promote social cohesion, inclusivity, a common sense of purpose, inspiration for children, and a general sense of happiness and distraction in the population, I’d make sure that I ran an international event like this every single summer…’

In medal terms, the Aussies won with a total haul of 178. And boy, didn’t we know it… Channel 7’s area of the IBC was bounded by a large blank wall that we all had to pass to get to the dining area. The wall didn’t stay blank for long. Everyday more A4 certificates were fixed to the wall championing the success of Australian athletes and teams, until eventually they ran out of space. It made me smile with happiness every single time I walked past it.

England came a close second with 176 medals, their best ever Commonwealth Games achievement, whilst Canada came a rather distant third, with 92 medals. But happily, lots of the other Commonwealth countries managed to achieve medals, too, and got their name on the Birmingham 2022 results table.

One of those countries was Niue, a small island country in the South Pacific. With the leader of the country – Premier Dalton Tagelagi – competing in the Games himself at Lawn Bowls, there would have been an added incentive for him to be the first athlete in their history to win a Commonwealth Games medal. But instead it was Heavyweight Boxer Duken Holo Tutakitoa-Williams that celebrated a bronze medal for him, Team Niue and his country.

On my terms, working on the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games was as near a perfect experience that I could have hoped for: mixing a live sport channel each day, to a global audience, from the city of my birth. How, I asked myself one day walking to work in the sunshine from my nearby hotel on the NEC site, can my personal life be so, er, challenging (I was dealing with the unexpected death of my father and away from Heather for 2 months), yet professionally, feel so blissfully happy? Is that shallowness on my part, meaning my work determines who and what I am as a person, I wondered? (Probably. Any other answers on the back of a $50 note please, to Hillman Household, Sinnamon Park, QLD 4073.) But whatever it is that these self-absorbed musings suggest, there’s one thing that I am certain of: Birmingham 2022 was definitely something all Brummies could be very proud of.

On my terms, working on the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games was as near a perfect experience that I could have hoped for: mixing a live sport channel each day, to a global audience, from the city of my birth. How, I asked myself one day walking to work in the sunshine from my nearby hotel on the NEC site, can my personal life be so, er, challenging (I was dealing with the unexpected death of my father and away from Heather for 2 months), yet professionally, feel so blissfully happy? Is that shallowness on my part, meaning my work determines who and what I am as a person, I wondered? (Probably. Any other answers on the back of a $50 note please, to Hillman Household, Sinnamon Park, QLD 4073.) But whatever it is that these self-absorbed musings suggest, there’s one thing that I am certain of: Birmingham 2022 was definitely something all Brummies could be very proud of.

The next Commonwealth Games, in 2026, returns to Australia, to the State of Victoria. We know that a lot can happen in four years (as we saw with Covid-19); and Birmingham will certainly be a hard act to follow… But believe me when I say that I’m ready put my hand up to be of service again to these most friendly games. I’ll be there like a shot, if I’m asked.

Coming up in the next edition…

Heather and I travel to Canberra by motorcycle: a nine-day round trip from Queensland (QLD), through New South Wales (NSW), to the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), travelling in the company of 4 other couples on motorbikes, to meet-up with 2,000 more bikes in the capital. There will be pot holes, floods, road kill and the most beautiful scenery you could possibly imagine; plus a visit to the receiving station from where television pictures of the first moon walk were relayed around the world.

Cover picture: Two of our grandbabies watching the output of the Commonwealth Games Channel on 7-Mate, with Nanna (Heather) at their home in Brisbane.

[All pictures © Neil Hillman 2022.]

I live and work on the lands of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and I recognise them as the Traditional Custodians of this country.

It’s good to read a story of sport doing what, ideally, sport should do. It will be interesting to see how the concept of the Commonwealth evolves further; hopefully it can continue on the path you’ve outlined above. (PS: please always nerd out on the audio aspect; I was quite curious how all that was parsed out for the broadcasts).

Hahaha! Thanks Jason!

I’m always cautious NOT to go into too great a depth about my work, for fear of ‘turning off’ readers; so hopefully any technical descriptions I do provide still remain ‘accessible’ and ‘readable’.

But I’m more than happy to spread my gospel of ‘sound consciousness’ at the drop of a hat!

Thanks for taking the time not only to read the blog, but also to comment… Kind feedback is a writer’s oxygen!

Kindest regards,

Neil.