The one in which Heather and Neil give peace a chance…

Two’s company, three’s a cluster

Our Etihad Airways 787 touched down smoothly on the rain-lashed tarmac of Kingsford Smith airport, having flown like an arrow at 250 metres per second through the Arabian night. We arrived with the disorientation familiar to any passenger that has endured a long-haul flight, having been transported once more into evening, this time in Sydney, and with no sense of a day having passed 6 miles beneath us.

Our Etihad Airways 787 touched down smoothly on the rain-lashed tarmac of Kingsford Smith airport, having flown like an arrow at 250 metres per second through the Arabian night. We arrived with the disorientation familiar to any passenger that has endured a long-haul flight, having been transported once more into evening, this time in Sydney, and with no sense of a day having passed 6 miles beneath us.

It had proven impossible to get ourselves into Queensland from the UK because Brisbane’s quarantine hotels were all at capacity; so instead, we opted gratefully for New South Wales and had to accept that at $4,000 (£2,185) the cost of our 14 days in isolation there was higher than the $3,700 bill we would have faced in our new ‘home’ state. On top of that we needed to add the cost of a hire car to make the 900-odd kilometre trip from Sydney to Brisbane… It will take some getting used to having road signs in English but distances in European units; and I found myself whiling away what turned into an epic drive by carrying out mental long division and converting each 10 kilometres into 6-mile units. What we had planned for after leaving isolation was a 3-day sight-seeing road trip, travelling north along the east-coast Pacific Highway to Brisbane, stopping overnight in three delightful hotels en-route: at Port Macquarie, Coffs Harbour and finally Byron Bay, a short hop from our destination. What transpired was something rather different. But first, there was our quarantine to complete.

Quarantine is a long-established and widely-adopted procedure that enforces a restriction on the movement of people – or animals or cargo – with the intention of preventing the spread of communicable diseases, by people who may be infectious, but do not have a confirmed medical diagnosis. Traditionally, sailing ships entering harbour would fly a yellow flag (the ‘Yellow Jack’ signifying ‘Quebec’ or ‘Q’ for quarantine in nautical parlance) if they had illness on board and were requesting quarantine. Today, the opposite is true: a ship will dock displaying either a single or a double yellow flag, to demonstrate to Port officials that they are safe to board and provide clearance for the ship’s crew, its passengers, or its cargo.

Therefore this – as well as Australia’s concerns surrounding Covid and its comprehensive Biosecurity Act of 2015 – was why as well as being kept in quarantine for 14 days on arrival, we had to show negative Covid PCR test results before we could leave the UK; and then agree to be tested again on days 3 and 8 of our confinement, interviewed by a doctor on day 13, and on release, find a place to be tested on day 16 after landing.

But notwithstanding all that, we reasoned that it would not be like hard labour: I mean, seriously, how hard could it be to spend two weeks in a comfortable hotel room, with 3 meals a day delivered to your door? Contrast that with ‘Typhoid Mary’ Mallon’s quarantine experience in America… Mary was an Irish cook who landed in New York in 1907, unknowingly infectious; and by continuing to work, she went on to infect 53 others, three of whom died. Mary was obviously successfully tracked and traced back then, because she was forcibly quarantined twice by the authorities, over separate periods that totalled a mind-boggling 30 years. The last 23 and a half years of her life were spent in medical isolation at the Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island: an institution dedicated to the containment of those afflicted by typhoid, polio and tuberculosis. Her memory, or perhaps her notoriety, lives on by the fact that she is the first recorded asymptomatic carrier of typhoid in America.

Being incarcerated on arrival in Australia is not a new phenomenon for English arrivals, ho-ho-ho; but if I can offer you one piece of advice on landing here for the first time, please do resist the urge to offer break-the-ice lines with officials such as: ‘Do I have Police record? Oh yes, I’ve got them all!’, or ‘A police record? I didn’t realise it was still a requirement!’, or worse still: ‘Haven’t I seen you on the telly in ‘Border Force Australia’?’ Trust me, they will not be impressed.

The capacity of an Etihad Boeing 787-9 is 336 passengers; 28 of whom can occupy the business class pods at the front of the aircraft’s huge fuselage. But on our flight, there were just 36 passengers, of which 7 joined us in our luxurious cocoon. Which meant aside from us receiving the most incredibly attentive service from the cabin crew, once we had cleared immigration and customs, had our temperatures taken and answered the medics questions, looking for all the world like a crocodile of primary school children on a day trip, we were escorted by the police to board a coach that would take us to our mystery hotel, and quarantine. I held Heather’s hand all the way.

It was dark, it was wet and I am unfamiliar with the Sydney suburbs, having previously only spent a couple of days on fly-in, fly-out business trips to Australian audio manufacturer Fairlight, situated in the outskirts of the city; so, the journey through those streets was a mystery tour. But after about half an hour, I recognized the distinctive ‘coat hanger’ bridge and my spirits lifted somewhat as we turned into the drive of the Marriott Hotel at Circular Quay. Some years earlier, we had spent a New Year’s Eve happily marooned amongst tens of thousands of other spectators on The Rocks by Circular Quay, watching the magnificent fireworks display that had heralded-in 2009.

‘A room with a view, and you, and no one to worry us…’

Seeking social distance, we had headed to the very back of the coach, which meant that we were last off in a time-consuming process that involved two people at a time checking-in at reception, recording their passport details with the police, and then being escorted with a luggage trolley to a hotel bedroom by military personnel. When we checked-in I was given the tiny cardboard folder that would normally hold a key card, and without thinking I pointed out that the key itself was missing; and then, not for the first time, I felt rather silly when it was gently explained that we would not need a key: because we would not be leaving the room until we checked-out in two weeks’ time.

At the check-in desk, I’d asked that if at all possible, please could we have a room with a nice view (it was all I could do to stop myself requesting a room with a balcony that overlooked the harbour) and obviously my doleful, pleading eyes (or perhaps my red-eyed, somewhat dishevelled state) must have melted the receptionist’s heart, because as views go from this hotel, we had a good one: looking down on Circular Quay and taking-in the full aspect of the bridge and part of the harbour; and beneath it, looking back at us from the far bank, was the huge, nightmarish ventriloquist dummy of a face that forms the entrance to the Luna Park fun fair.

As soon as the door shut behind us, we both headed straight for the large picture window; and the sight was spectacular: pinpricks of colour from vessels criss-crossing the harbour, lights from the traffic driving across the bridge forming red and white dotted lines that chased in opposite directions and the bridge itself, which displayed a red beacon at the top of its arch. Over the next few days, we would look out at this sight at all times of the day and night, as the mental gyroscope of jetlag continued spinning our body clocks around our home time zone and crept slowly towards stabilisation on our new daylight hours.

It is suggested that it takes a day per hour of time difference for your system to re-calibrate, and previous experiences of travelling to and from Australia, or in the opposite direction, to and from the US for work, hadn’t allowed me the luxury of uninterrupted time to adjust: I had to get into the swing of things straight away; but this was going to be a very different period of time, one that would allow us to get re-adjusted to the 10 hour time-difference at our own pace.

With no imperative to achieve anything by a certain time, we were all over the place – some days we did not even get dressed, an unimaginable state of affairs ordinarily. We would shower, become exhausted by the effort of it all, and promptly fall asleep again. It was hard to concentrate on anything for any length of time, so my projected pageant of reading, writing, listening and viewing for a solid two weeks somehow evaporated away in a fug of broken sleep and aching muscles, brought on by an unusual degree – even for me – of slothful inactivity. Later on in our confinement, we would exercise: Heather pacing the room in 30-minute stints on an elliptical walking track she constructed between the door and a coffee table near the window, me with half-hearted stretching and half-speed Karate kata; but whilst Heather quietly sewed, for me the first couple of days were spent in one of two extreme states – either semi-comatose or with an inappropriate level of alertness only otherwise achieved through ingesting industrial levels of a performance enhancing drug. I could have either modelled for a reprise of The Death of Chatterton or won this year’s Tour de France… Neither of which, irritatingly, were particularly comfortable or comforting to me. Heather, it has to be said, has saintly levels of patience; and a raised, quizical eyebrow was all that it took for me to realise that perhaps I was saying or doing something strange, Again.

Blue jean baby, seamstress for the band

Video calls to the grandchildren

Our days revolved around three anchor-points: breakfast, lunch and dinner. It would be unfair to say that the food was poor, because clearly a lot of thought went into it – and we could not complain about the calories we consumed over a day, either; but the quality was disappointingly inconsistent; especially when these were the day’s high-points. I felt disgracefully first-world ungrateful with my attitude at times, justified it by remembering that we were paying $130 (£71) a day for our food, but then felt first-world ashamed all over again by realising just how incredibly fortunate I am.

Breakfast was either a packet of cornflakes with a carton of milk and a small bottle of fruit juice, or a packet of Granola and a small yoghurt pot and fruit juice; although a couple of times we had a toasted bacon and scrambled egg sandwich each, which by the time we got it was understandably tepid, despite the thermal box it arrived in. We did better with lunches, having some genuinely delicious dishes such as chicken Caesar salad, Vietnamese spring rolls or a cheeseburger; whilst dinner included appetising things like a lamb shank, a salmon fillet and on one glorious, memorable occasion, a truly stunning rare steak. Clever Mrs. H had carefully packed two china dinner plates and proper cutlery into our luggage, so we wouldn’t be eating out of cardboard cartons with wooden ‘sporks’ for a fortnight. A glass of wine here and there might also have gone down well with dinner, but as an experiment we went dry (which was no hardship for Heather who barely drinks alcohol); however, I rather surprised myself by not feeling any sense of deprivation. Quite amazing.

The loud double knock on the door that announced that our food was waiting on the conference room chair placed outside our room always made us jump, and for a few days I thought it was simply hilarious to shout back ‘Who’s there?’ (In the spirit of: ‘Knock-knock’ – ‘Who’s there?’ – ‘Dinner!’ – ‘Dinner who?’ – ‘I dinner know who you are, but your food is here!’) (I had quite a few hours to think up that Christmas cracker of a joke.)

Special breakfast

Special lunch

Special measures

The routine for collecting our food was printed as a reminder on the inside of our door, and it said something like ‘put on mask, wait for 1 minute after the food arrives before opening the door, close the door as quickly as possible after collecting the food’. We never did see who delivered our food because they clearly possessed ninja skills. Our only other contact with fellow humans was when the nurses called to take our Covid swabs on days 2 and 8, and then when the doctor talked to us on day 13, gave us our quarantine completion certificates, and a letter from the police that provided us with permission to travel.

‘This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning’

On day 10, it was as if a switch had been thrown: we slept through the night, awoke fresh and generally started to feel better. Throughout our days locked in our room, the view through the window remained compelling, aided by the fact that directly opposite us, a glass-fronted office block was being constructed. The aerial ballet of cranes lifting girders and delicately manoeuvring huge sheets of glass into place was captivating, if not somewhat alarming, with the ‘What if?’ question rattling around my head. According to a Google reference we found, more steel was going into this office block than went into the Eiffel Tower; and that is not surprising, it is an immense construction. The Salesforce Tower (a name purchased by the world’s leading CRM software firm, who will be a key tenant) is being built by Australian construction firm LendLease, and it will be Sydney’s tallest building at 263 metres. With a metaphorical little wave of the Union flag, I was curiously pleased to discover that its revolutionary ‘green’ design comes from British architects Foster + Partners.

The Sydney Salesforce Tower takes shape

Our last couple of days were spent beginning to imagine the first activities we would get up to once we were free… We arranged dinner with friends for our first night of freedom, breakfast the next day with a professional colleague of mine; and then lunch with a friend at one of the pavement cafes in The Rocks area, alongside the dock where the grand ocean liners berth.

The act of leaving our room, for the first and the last time, was all rather strange. We both felt a certain apprehension about re-joining the normal world, but we need not have worried – the outside world was still anything but normal; and given how organised everything had been leading up to us arriving and going into the room, our departure was nothing less than organised chaos. We had been asked by a man with a clipboard what time between 4pm and 6pm we would like to check-out, suggesting that the decamping of we detainees was going to run at staggered times, with the precision of a military operation. Naturally, we had requested 4pm; and so it seemed did everyone else who had been on our flight. Because a dozen of us stood in masks clustered tightly together in a narrow hotel corridor, waiting to enter the elevators that gaily sailed past, up and down, despite the disinterested and periodic prodding of lift buttons by the security guards, who were marshalling us without either masks or any obvious enthusiasm. Our two weeks of isolation was put into serious jeopardy by this half-an-hour of utter, mind-numbing, stupidity. In this way are Covid-clusters created and then all-too-easily blamed onto international arrivals leaving quarantine hotels. I was as jumpy as hell as we left.

Gluten-free indulgence

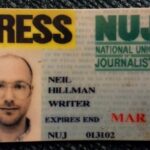

To us, more valuable than a Glastonbury pass

But leave we eventually did, checking out first with the police and then the ever-obliging Marriott reception staff. We had one night left in Sydney before we would set off on our road trip north; and that would be spent at the delightfully elegant and confidently understated Intercontinental Hotel, just a 5 minute walk away for those who might be unencumbered with two 30Kg suitcases, laptop bags and carry-on handbags. We however took a $10 taxi ride; it had already been a long day.

Coming up…

At 11am on our first day out of quarantine, Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk announced a snap closure of the state border with New South Wales, starting later that day. We found ourselves with just 12 hours to collect a hire car and drive the 900-plus kilometres to Brisbane, or face yet another 14 days in a quarantine hotel, at our own expense…

Cover picture: Jet-lag dawn. The view from our quarantine hotel room at the Sydney Harbour Marriott. [All pictures © Neil Hillman 2021]

I live and work on the lands of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and I recognise them as the Traditional Custodians of this country.